Like many visionaries, the founders of Radburn needed well-heeled patrons. They found them among the nation’s most famously monied names, including Lehman, Harkness, Warburg, Morgan and, most importantly, Rockefeller.

Radburn’s developer, the City Housing Corp., was formed in 1924 to build an affordable “garden city,’’ safe from cars and free of congestion. Its board members and investors -- a financial and philanthropic Who’s Who -- were one reason the “Town for the Motor Age’’ was a sensation when announced in 1928.

“It is quite a thing,’’ wrote housing reformer Louis H. Pink, “to be associated with the City Housing Corporation.’’

Its supporters consisted of three overlapping groups: CHC board members, such as William Sloane Coffin Sr., Douglas Elliman and V. Everit Macy; members of the advisory board, such as Eleanor Roosevelt; and investors, who included future President Herbert Hoover and John D. Rockefeller Jr.

Rockefeller invested more than $1.7 million ($31 million today) and loaned millions more, making him by far the CHC’s largest financier. And his commitment attracted other wealthy investors.

But Rockefeller only came aboard because of his confidence in the financial and managerial leadership of one man: Alexander M. Bing.

A Park Avenue fortune

Alexander Bing and his brother Leo had made a fortune building luxury high rise apartment houses on Park Avenue before World War I. During the war Alexander was a dollar-a-year government advisor. Afterward, he was looking for a new challenge.

A family friend, the architect Clarence Stein, sold Bing on his vision of an American garden city. To that end, in 1924 Bing formed the CHC and set about attracting support.

He had a special challenge. The CHC was organized as a “limited dividend’’ company – investors would get no more than a 6% yearly return on investment. Any excess funds would be deployed to build more garden cities.

A “limited dividend’’ was a particularly tough sell in the get-rich-quick Roaring Twenties, when the economy was booming and stocks were soaring. (The real total return for the Standard & Poor’s Composite Index, including dividends, from 1919 to 1929 averaged 20 percent a year.)

Moreover, big investors generally eschewed the housing market; residential construction was viewed as a disorganized and unreliable industry.

Yet by the end of 1926 Bing had raised about $1 million from 520 investors, including Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover, who committed $10,000.

Bing traded on the eagerness of many of the rich to do good while doing well – what’s now known as “social investing’’ – and to make clear that the excesses of the Gilded Age (1880-1900) were past.

Take Rockefeller Jr., son of the oil monopolist that historian Taylor Branch has called “the colossus of the robber barons.’’ Although much of his epic philanthropy can be attributed to his Christian beliefs, it also addressed a public relations problem.

He had been implicated in the massacre of 21 people in 1914 during a coal strike against a company in which the Rockefeller family had a stake. Advisors told him he needed to project a more benign image.

By 1929 Rockefeller Jr, was worth about $1 billion ($18 billion today). While he gave away much of that fortune, he didn’t do so indiscriminately. In the case of City Housing, he seems to have been persuaded to invest by the progressive economist Richard T. Ely (who later moved to Radburn).

In a letter to a Rockefeller advisor, Ely wrote that, despite misgivings about whether private philanthropy could solve the housing problem, “a concrete demonstration near NYC would attract a great deal of attention and … make a profound impression upon the country.’’

And Ely said Bing was the man for the job – “a hard headed businessman of large experience.’’

Investing in a good cause

Rockefeller’s investment helped set off a chain reaction among a class that belonged to the same clubs, attended the same schools, worshiped in the same institutions, served on the same boards and lived in the same neighborhoods.

Some were connected by their inheritances. Rockefeller, Macy and investor Edward Harkness all were sons of original investors in the Standard Oil monopoly, which eventually was broken up by the government.

CHC supporters included many notables, including:

Investor Betsey Roosevelt, one of Boston’s three famously charming and beautiful Cushing sisters – and daughter-in-law of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Director Johnston DeForest, an investor and amateur yachtsman known as “the old fox of Long Island Sound.’’ In 1931 he took his eight-meter boat Priscilla III to Scotland, where he won the famous Clyde Fortnight competition.

Alice Naumburg Proskauer, a director and wife of one of New York’s foremost jurists. She helped found the Euthanasia Society of America, an early right-to-die group.

Many CHC supporters displayed a social conscience at odds with the zeitgeist of the Gilded Age. For example, Anne Morgan – daughter of banker J.P. Morgan – was a union supporter who joined picket lines set up by striking female garment workers.

The CHC also was supported by institutions founded by Gilded Age millionaires, including the Carnegie Foundation (endowed by steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie) and the Russell Sage Foundation (based on the fortune of the financial speculator).

Their investments, as it turned out, did not produce the success Richard T. Ely had forecast; the Depression forced the company into bankruptcy in 1934.

Alexander Bing lost hundreds of thousands of dollars. But residents of the CHC’s communities – Radburn and Sunnyside Gardens in Queens – were hit harder than its investors. The latter lost money; the former, unable to keep up with mortgage payments, lost homes.

After the CHC bankruptcy, Bing continued to do business as “Radburn Inc.’’ The company gradually sold off most of the land the CHC had bought for what was to have been a community of 25,000, and finally dissolved in 1954.

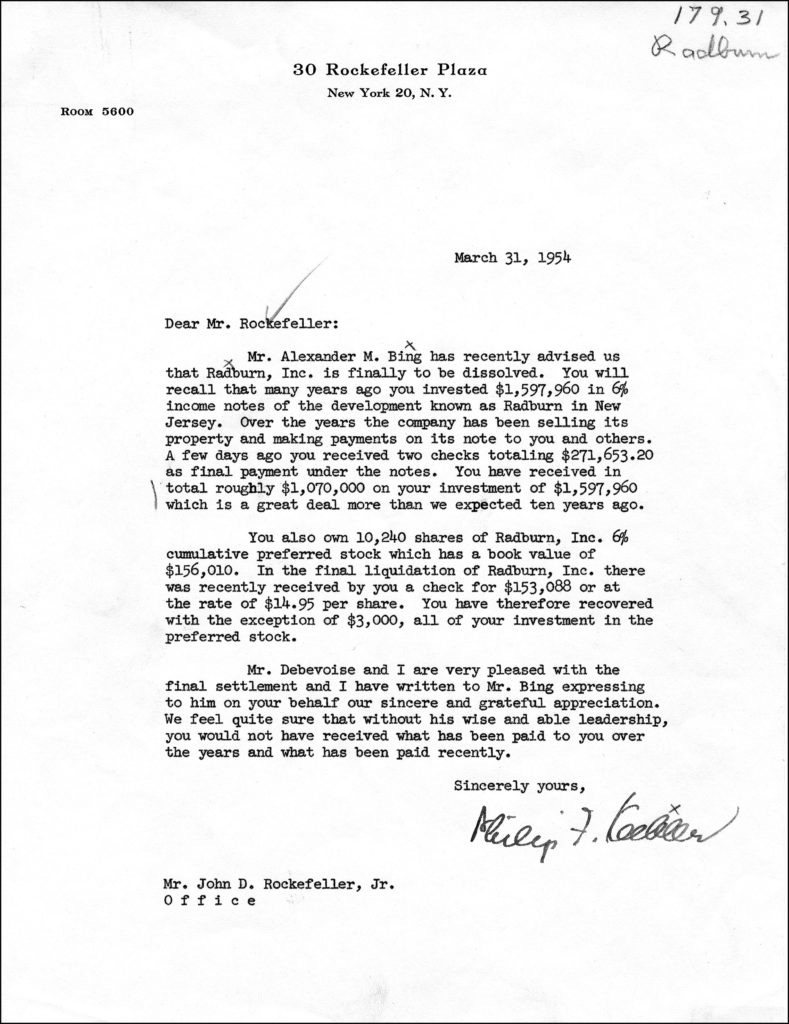

What of John D. Rockefeller’s investment? In a memo dated March 31, 1954, one of his lawyers informed the philanthropist that, despite City Housing’s woes, he had been repaid “a great deal more than we expected,’’ including “almost all your investment’’ in stock.

The lawyer continued: “I have written to Mr. Bing expressing on your behalf our sincere and grateful appreciation … for his wise and able leadership.’’

In the end, Rockefeller had done well by doing good.

Contributing: Jack Hampson

Nice to know that women like Betsey Roosevelt were involved in such a great town!

Learning so much about Radburn..the town in which I grew up and still feel is magical!!!