In the “Town for the Motor Age,’’ a runaway car and a heroic sacrifice

The story of Radburn’s first pedestrian death

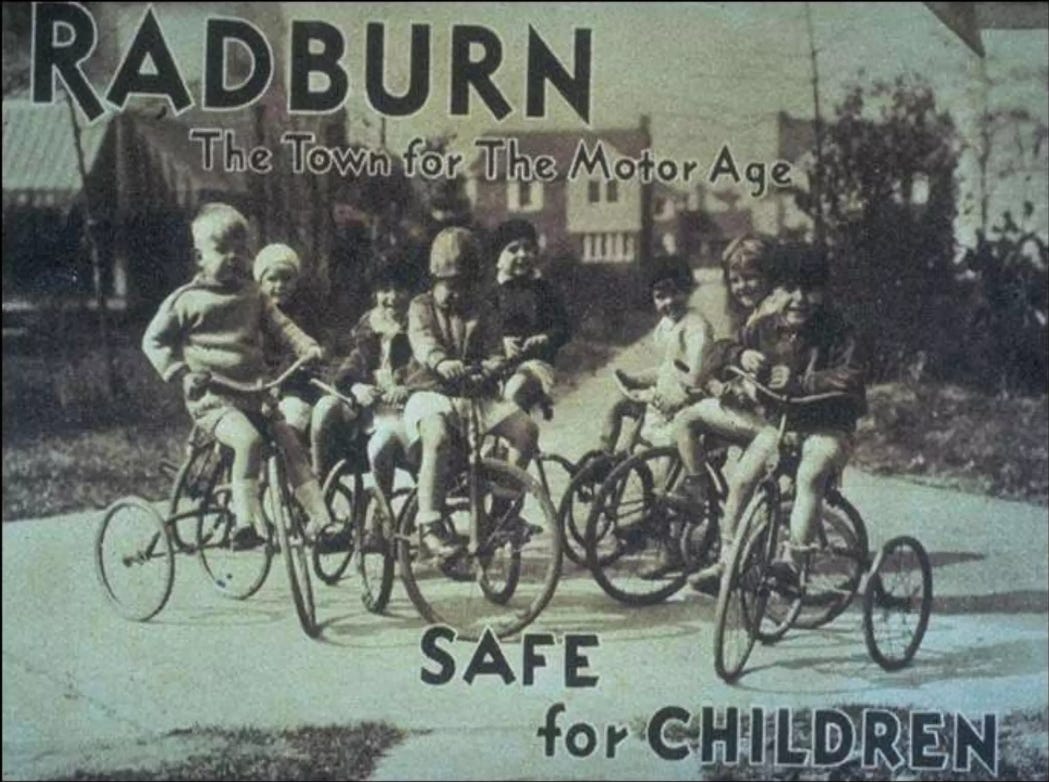

Early Radburn advertised itself as “The Town for the Motor Age … Safe for Children.’’ But on a late July afternoon in 1931, all that redeemed those promises was one man’s heroic sacrifice.

His name was Lloyd Wynne, and his act of selfless courage cost him his life.

It all started Sunday July 26, when Stanley Mackenzie pulled his car to the curb outside his second floor apartment at 322B Plaza Road North. He had two passengers: His wife Georgia, in the passenger’s seat, and her friend, Violet Tamplin, who sat between them. Stanley hopped out of the car and ran inside to change out of his wet bathing suit, leaving the women in the car with the engine running.

Georgia would later tell police that, while they were waiting for her husband’s return, she was asked by Tamplin to show her “how the car ran.’’ To do so, she “climbed toward the driver’s seat, and in doing so essentially placed the car in gear, ‘’ according to police.

The vehicle lurched forward and raced onto the grassy strip down the center of Plaza Road.

Across the street, at 317 Plaza Road, three small children -- the siblings Patsy and Michael Fox, and their cousin David Stolberg – were having a picnic on the lawn of the Fox family home. The car roared across the median, into the northbound lane of Plaza Road, and toward the children.

Lloyd K. Wynne, 31, who lived a few doors away at 6 Brighton Place, was standing nearby. He saw what was about to happen.

As the car bore down on the children he lunged in front of it, pushing the kids out of the way. The car slammed into him, smashing him against the porch.

Then it kept going. It continued into Brighton Place, a cul de sac off Plaza. It collided with a parked car, sustaining a punctured tire, but rolled on. The car finally was brought to a halt by a 9 Brighton resident who hopped onto the running board, reached inside the driver’s window, and turned off the ignition.

Dr. Albert Ewing was summoned from his Radburn home to attend to Wynne, who had massive internal injuries. He worked on him through the night at Paterson General Hospital. But by morning Lloyd Wynne was gone.

Wynne, who had been a clerk on Wall Street, left his wife, Lillian, and a 4-year-old son, Lloyd Jr.

The funeral service was held at the Wynne home on Brighton Place. It was conducted by Edwin Carson, rector of Christ Episcopal Church in Ridgewood. Although there is no record of his eulogy, which the Paterson Morning Call described as “touching,’’ Carson could not have failed to cite the most obviously relevant scripture, John 15:13: “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lie down his life for his friends.’’

A wrongful death

Michael Kuiken, a Bergen County prosecutor, charged both MacKenzies with manslaughter. A judge set bail at $1,500.

The outcome of their case is not known. But in May 1932 Lillian Wynne’s $50,000 civil suit against the MacKenzies for wrongful death was settled for $16,500 – about $379,000 today.

We don’t know what became of Lloyd Wynne’s widow or young son, or the MacKenzies. But neither the Foxes, the Wynnes nor the MacKenzies stayed long in Radburn.

The July 26 accident was the first fatal pedestrian accident in Radburn, which was planned to be a haven for pedestrians -- protected from vehicular traffic by a system of footpaths and cul-de-sacs. Pedestrian safety was not a trivial issue; in the mid-1920s, children hit by cars were dying at a rate of one a day in New York City.

In 1949, Radburn’s co-designer, Clarence Stein wrote that in the previous 20 years Radburn had had “only two road deaths. Both were on main highways, not in the lanes (cul-de-sacs).’’ As of 2024, that still seems to be the case.

One of the “main highway’’ deaths must have been Wynne’s. The 1931 accident did not occur on a cul-de-sac integral to Radburn’s vaunted “Safety Street Plan,’’ but on a peripheral through road (“main highway”).

While Radburn prided itself on its “houses turned around,’’ with yards and gardens isolated from vehicular traffic, the house outside which the children were picnicking fronted directly on the street, without even a sidewalk.

A lost dream

Given Radburn’s advertising about pedestrian safety, Wynne’s death would have been a public relations disaster, had not a far greater disaster already arisen – the Depression. By 1934 the company was bankrupt, and the dream of making the separation of cars and pedestrians a standard feature of American suburbia was lost.

Today, what endures is the example of a young father who, when the Radburn plan failed, gave his own life to save the children of others.

What became of the lives saved by Lloyd Wynne’s heroism? We don’t know about Patsy Fox, who was 7, or brother Michael, 2. But their 3-year-old cousin, David Stolberg, who lived in Manhattan and was visiting his Radburn cousins that day, made the most of his second lease on life.

He served as an Army combat reporter during the Korean War, where he escorted Joe DiMaggio on the baseball star’s visit to the front lines.

After the war Stolberg joined Scripps Newspapers, where he reported from Washington and abroad before ending his career as one of the chain’s top executives. He also founded the Society of Environmental Journalists, which each year honors in his name an SEJ member for exceptional volunteer work.

David Stolberg died in 2011 at 83. One of his favorite expressions was, "Life is a banquet, and most people are starving.’’ And, as his obituary put it, “he would roll up his sleeves and prepare a banquet for them.’’

This is a terrific story and I can see manslaughter, it was certainly negligence and only a hero saved those children, which would have been quite tragic. I love the color photos you have here, especially showing Brearley Crescent in developement where I lived as a kid, I remember the overgrown empty lot across the street where we played, a great memory, thanks.

I really enjoy your articles. Thank you!