The golf champ who fell to Radburn

Cyril Walker won the 1924 U.S. Open. It was downhill from there.

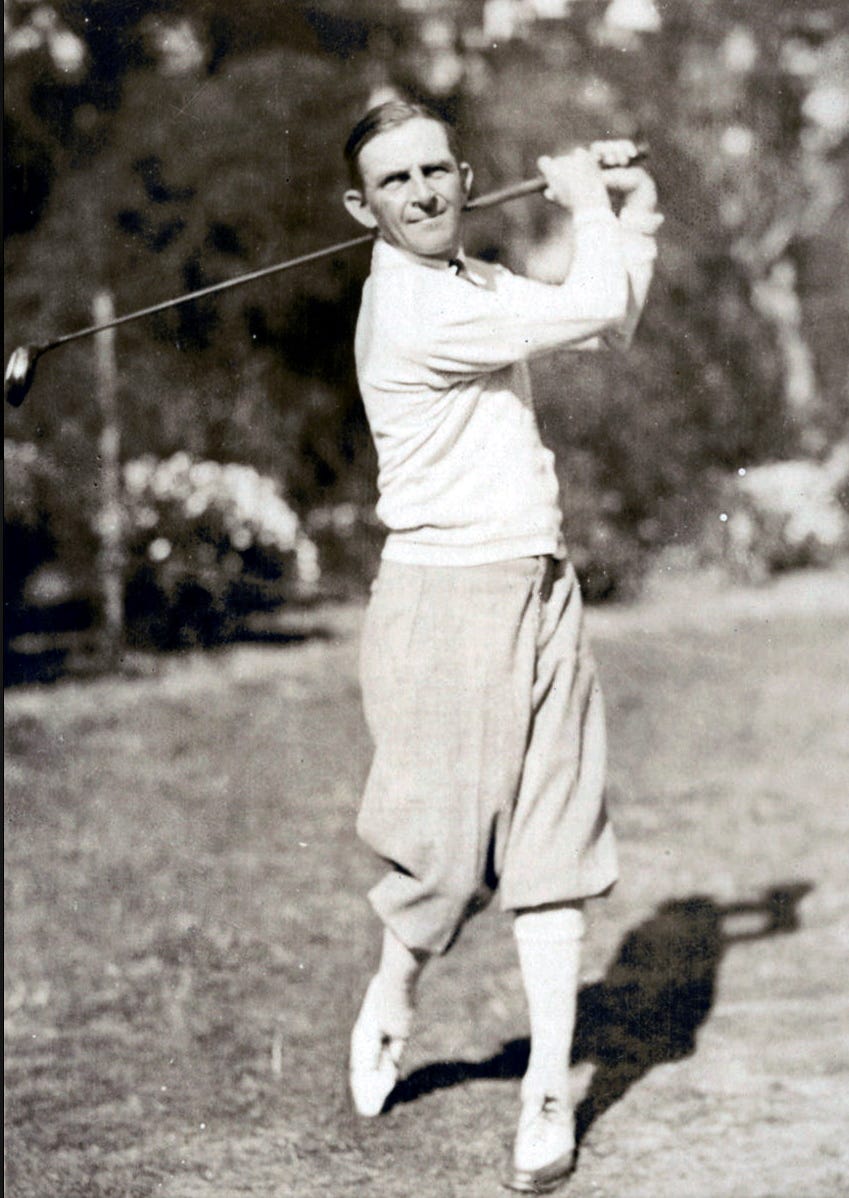

1924 U.S. Open Champion Cyril Walker

In 1934 Radburn was home to many accomplished people, from the dean of American economists to the operator of the world’s largest X-ray machine. And there was Cyril Walker – 1924 U.S. Open golf champion – who was once more celebrated than any of his neighbors.

But the story of what happened to Walker after his tournament victory is one of the most tragic in the history of American sports.

The Englishman came out of nowhere to defeat the great Bobby Jones for the national golf title. But by 1934 he had blown through a small fortune and worn out his welcome in golf with poor sportsmanship and slow play.

He eventually would die, homeless and alcoholic, in a Hackensack jail where he’d sought refuge on a stormy night.

That was 1948. Fourteen years earlier, Walker at least had a home – a rented apartment at 338 Plaza Road North in Radburn.

338 Plaza Rd. North (unit with flat roof), where the golf champion once lived

Cyril Walker was born in the English industrial city of Manchester in 1892. He supposedly discovered golf as a boy while retrieving a soccer ball from the confines of a course. He began to caddy, used his earnings to buy some clubs and came to believe he could make a living at the sport.

After some success in England, he immigrated to the United States shortly before the First World War and became the pro at several clubs, including the Englewood Country Club in Bergen County.

Walker’s most notable feature was his size, or lack thereof. He stood 5-6 and weighed 120 pounds, and looked even smaller; “frail’’ often was used to describe him. But he had exceptional timing, and could hit a ball, as sports writer Grantland Rice would put it, like he was “cracking a whip.’’

Walker won several state open championships, and reached the semifinals of the PGA tournament in 1921, defeating one legend (Gene Sarazen) in the quarterfinals before losing to another (Walter Hagen). But in an era dominated by Jones, Hagen and Sarazen, he was an afterthought – until the ‘24 Open.

The tournament was held at the Oakland Hills Country Club outside Detroit. The course was notoriously long – it was nicknamed “The Monster.’’ No one gave the diminutive Englishman a chance, including himself.

The winner, Walker told a reporter, “will be a big fellow with the physical strength to stand the strain. … It’s too much for me. The course is too big.’’

After three rounds, however, Walker was tied with Jones for the lead. During the final round, the wind picked up, making the long course even longer. But the low drives Walker had perfected playing on links courses back on the Irish Sea were ideal for such conditions.

On the difficult 16th hole, Walker changed clubs three times before hitting an approach shot that landed just eight feet from the hole. British golfer Tommy Armour called it the greatest shot he’d ever seen. Walker then sank a birdie putt and ended up beating Jones by three strokes.

Walker won about $150,000 in prize money and endorsements – equal to about $2.8 million today. He embarked on a series of lucrative exhibition matches, endorsed golf equipment and had a syndicated newspaper column. In 1926, he was selected to play on the U.S. team in the inaugural Ryder Cup competition with Great Britain.

Then, for reasons unclear, the champ’s life and career began to fall apart.

From champ to caddie

In competition, Walker played more and more slowly. He’d inspect greens for any imperfection; repeatedly check the wind; take countless practice swings. According to legend, golfers on the course behind him were given decks of cards so they could play solitaire while waiting for Walker to play on.

Walker also became increasingly irascible. At the 1929 Los Angeles Open, when an official threatened to disqualify him for slow play, he shouted, “You won’t disqualify me – I’m Cyril Walker! … I’ll play as slow as I damn well please.’’ When he refused to leave the course, police were called in to hustle him off.

After the stock market crash of 1929 wiped out Walker’s investments, he got a job at the Saddle River Country Club in Paramus. But in 1931 he was arrested for malicious mischief after the neighboring Orchard Hills Golf Club accused him of destroying its road signs. He was released on $500 bail.

Around the same time he was accused of beating a caddy with a golf club; the charge was dismissed for lack of evidence.

In 1934, as a former Open champ, he was invited to join the 61-man field in the first Masters Tournament in Augusta, Georgia. He came in last. It was his final major.

Cyril Walker and 1924 U.S. Open Cup

That also was the year Walker moved to Radburn, where his troubles continued.

In June, Walker was arrested in Ridgewood for drunk driving. He told police he was broke and was going to the bank to withdraw his last $40.

The Bergen Evening Record reported that Walker, “noted for temperamental outbreaks’’ on the course, made “an eloquent plea for leniency after pleading guilty.’’ He told the judge he hadn’t held a job in three years.

Someone – probably his brother Will, who lived in Teaneck – came up with the $250 fine to spare Walker three months in jail. His license was suspended for two years.

A few months later, the Radburn resident was back in the news. A former Pinehurst, North Carolina, hotel employee named Macy McSwain sued Walker for $100,000 for breach of promise and “seduction.’’ She said he proposed marriage two days after they met in February and drove her to New Jersey. There, she learned Walker was already married. He was detained and released on $4,000 bail.

Then he dropped out of sight.

In 1940 a reporter found Walker in Miami Beach, working as a caddie at a municipal course and sleeping in a Salvation Army shelter for 25 cents a night. He always wore the same torn maroon turtleneck sweater, even on the hottest days, because it was the only shirt he owned. He was estranged from his wife and son; he had a drinking problem; and he told the reporter he hadn’t played golf in four years.

Around the same time the Atlanta Journal golf writer O.B. Keeler spotted Walker in the spectators’ gallery at a minor tournament in Miami, “a pathetic, skinny, ragged figure.’’

By the mid 1940s Walker had moved back to New Jersey, where he worked in Hackensack as a restaurant dishwasher and stayed at the local YMCA.

On the night of August 5, 1948, Walker walked into Hackensack police headquarters, seeking a night’s lodging. He spent the night in a cell with several vagrants and was found dead the next morning, slumped over a chair. The cause of death was pneumonia. He was 55.

The former Open champion was buried in a potter’s field.

Walker in Radburn

Walker apparently lived in Radburn for less than a year. Did his neighbors know who’d moved into their midst, or that he’d suffered so many reverses?

Walker once claimed to suffer from chronic intestinal inflammation that contributed to his other woes. “The American custom to hurry was my undoing,’’ he wrote. “Crowded days undermined my health.’’

Radburn, “The Town for the Motor Age,’’ had been designed to mitigate the bustling pace that Walker found debilitating. But residing there seems to have done him little good. And shortly before he moved out, Radburn’s developer declared bankruptcy – a victim, like Walker, of the Great Depression.

Sad story but well written and very interesting.