WHAT’S SPECIAL ABOUT RADBURN

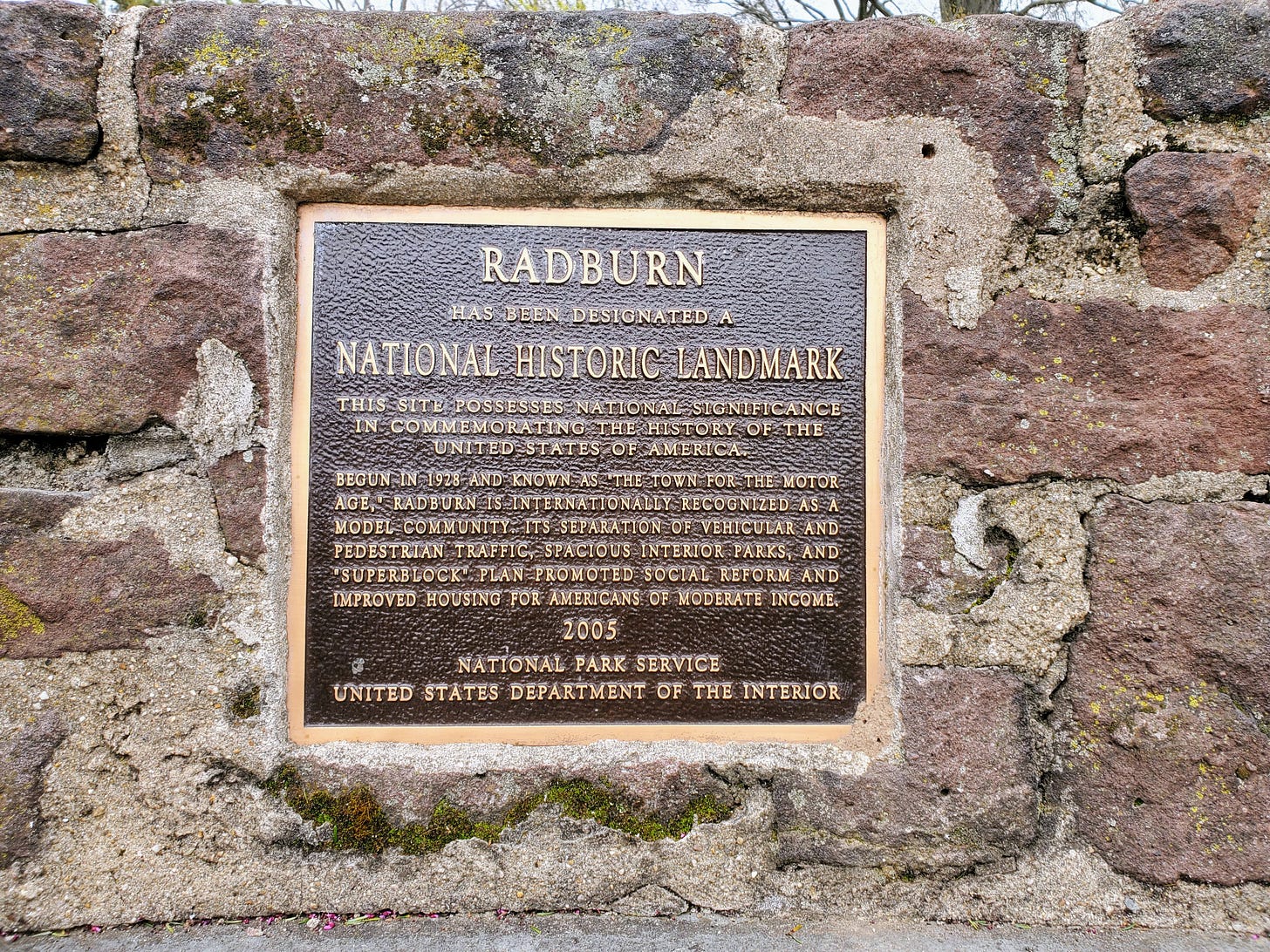

Welcome to this site devoted to the fascinating story of “The Town for the Motor Age.’’ That’s what its creators called the community that they began building in the spinach fields of Fair Lawn, New Jersey, almost a century ago. It immediately became the nation’s most aggressively promoted and eagerly anticipated planned suburb.

The new settlement was called Radburn, Scots for “swift brook’’ – a reference to the nearby Saddle River. Its planners envisioned a community of 25,000, with three elementary schools, recreation centers and shopping districts; a high school and public library; offices and factories.

This famously planned community, however, did not turn out as planned. But so bold was its original vision that, even in truncated form, Radburn has become one of only about 2,600 National Historic Landmarks; the inspiration for new communities around the world; and part of the education of every architect and planner.

Most of all, Radburn reminds us of the power of idealism – that, sometimes in some places, people build not simply to make a bigger profit, but to make a better place.

The story begins in the early 1920s, with two crises in American life: of the city, and of the car.

Cities were increasingly polluted, noisy and congested. Manhattan’s squalid Lower East Side, for example, had the highest population densities on the planet.

These problems were exacerbated by the car. Each year millions of new vehicles spilled onto streets designed for horses or trolleys. With few streetlights, stop signs or traffic rules, the result was mayhem.

And the mayhem was murderous. City children, who played in the street, weren’t experienced at avoiding cars; drivers weren’t experienced at avoiding kids; hospital care for head trauma was primitive. One study found that children were being hit and killed in New York at a rate of one a day.

Two men – architect-planners named Clarence Stein and Henry Wright – saw a solution: garden cities.

England’s first garden city, Letchworth, was developed early in the 20th century as a reaction against London’s sordid slums and satanic mills. Letchworth was low-density and self-sufficient, with housing, factories, schools and playgrounds.

Stein sold this idea to his friend, the real estate developer Alexander Bing. In 1924 Bing formed the quasi-philanthropic City Housing Corp. to build an American garden city.

After a successful experiment with its Sunnyside Gardens development in Queens, the CHC purchased a site in rural northern New Jersey and in 1928 announced plans for Radburn. The story made the front page of The New York Times, and fawning editorials appeared in scores of newspapers.

Radburn became a national sensation because of investors and advisors, including the likes of John D. Rockefeller Jr. and Eleanor Roosevelt; because of its startling plan, with cul de sacs and footpaths to separate pedestrians and cars, houses turned around away from the street, and attached garages; and because of innovations such as a homeowners’ association and a legal scheme to preserve parkland in perpetuity.

Above all, Radburn was news because it claimed to be the future -- the way Americans would live as suburbs spread across the landscape. And who isn’t interested in the future?

But just six months after Radburn’s first residents moved in, the stock market crashed. The ensuing Depression drove the CHC into bankruptcy and wrecked the dream of a community of 25,000 that would be the template for American suburbia.

The Radburn plan, to be sure, was flawed. It anticipated the “motor age,’’ but not the three-car family and its parking needs, nor kids’ determination to bounce balls and ride bikes on streets supposedly reserved for cars.

And although Radburn was unusual at the time for its range of housing for various income groups, it was typical in excluding people of color.

Radburn today, with a population of around 3,500, is a fraction of what was planned. But it is no less compelling for those who like to walk, who want to know their neighbors, or who appreciate Radburn’s signature tradeoff: smaller yards in return for beautifully landscaped parks in the heart of its “superblocks.’’

This blog tells Radburn’s story in profiles, vignettes, and videos. They portray a community that refused to die, and that remains fascinating for what it became, and for what it did not.